October 16, 2024

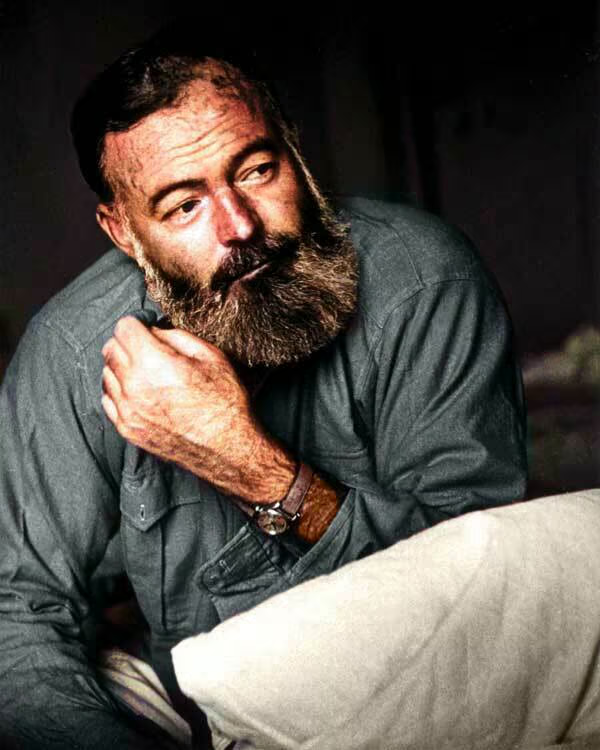

Ernest Hemingway was a battle-hardened writer. He hunted lions, fought bulls, faced off against professional boxers, and survived not one but two plane crashes — not to mention the action he saw in two world wars!

He was a man who didn’t just yearn for adventure, but who thrived in the midst of it.

Yet for all the adventure Hemingway enjoyed in life, it was World War I in particular that shaped him into the man he grew to be. His experience reveals how the atrocities of war first broke him down, and then built him up into one of the most formidable literary spirits of the 20th century.

This is the story of Hemingway’s baptism by fire in the First World War, and what it can teach you about thriving in the midst of hardship…

The story begins when Hemingway was 18 years old, writing for a newspaper in Kansas City. He had no fame, fortune, nor prestige to his name, and was eager for an opportunity to prove himself.

When World War I broke out, Hemingway tried to enlist, but was too young to do so without his parents’ permission. Looking for a way around the red tap, he got creative — and eventually found the loophole he needed.

It came in the form of the American Red Cross, which allowed him to volunteer as an ambulance driver in Italy. Hemingway signed up, and in June 1918 he boarded a grimy French steamship en route to Milan, where he would volunteer to serve the allies.

It didn’t take long for Hemingway to experience the horrors of war. On his first assignment he was sent to provide aid to a bombed munitions plant — and there he found bodies strewn everywhere.

He later wrote, “We carried them in like at the General Hospital in Kansas City.” Though Hemingway considered this experience his “baptism of fire,” he didn’t let the horrors of war destroy his enthusiasm and desire to succeed. Instead, they strengthened his resolve to serve on the frontlines.

Hemingway finally witnessed real military action while serving in the Northern Italian villages of Fornaci and Fossalta. There he was tasked with handing out provisions to Italian soldiers, but it was far from a simple charity operation. The young Hemingway had to travel through active war zones on a bicycle — dodging fire fights, sharpshooters, and artillery blasts along the way.

Inevitably, he got a little too close to the action. On July 18th, 1918, an Austrian mortar shell landed a mere few feet in front of him. As he later described the experience:

“There was a flash, as when a blast-furnace door is swung open, and a roar that started white and went red.”

The mortar blast sent 200 pieces of shrapnel into Hemingway’s body, knocking him out cold…

After several minutes, Hemingway slowly began to regain consciousness. He heard a nearby soldier crying out in pain, and slowly made his way over to him. Despite the pain from his shrapnel-riddled body, Hemingway hoisted the soldier up and slung him over his shoulder. He then began a long, painful journey back to the medical tents.

Bullets whizzed around him as he made his way back. As darkness began to fall, he was struck in the leg by machine gun fire and stumbled over. But with adrenaline surging to numb the pain, he rose to his feet again — and about an hour later, with his strength nearly exhausted, he arrived safely at camp.

There Hemingway and the rescued soldier received life-saving aid. The event marked the end of Hemingway’s service in the war, but not before his efforts were recognized by the Italian government — it awarded him the Silver Medal of Valour for his efforts.

While most men were understandably traumatized by the horrors of the First World War, Hemingway thrived off them. It was through these horrors that he began to form the philosophy that would later permeate his writing:

“The world breaks everyone, and afterwards many are strong at the broken places.”

Hemingway’s attitude in the face of evil wasn’t why do I suffer? but rather how can I rise to the occasion? He viewed the traumas of war not as senseless horrors sent to destroy him, but as opportunities to prove that a strong spirit can overcome anything.

It was this same spirit that sent him on a lifetime of adventures, and inspired many of the 20th century’s most beloved novels…

When red tape and age restrictions threatened Hemingway’s chances of heading to the front, he got creative. He hunted for work-arounds and eventually found one that helped him achieve his goal. Instead of accepting defeat, he got creative — and his creativity led him to his life’s adventure.

World War I traumatized millions of young men. It was a brutal war of unspeakable terror that created the “lost generation.” But for Hemingway, these same horrors molded his manhood.

Even when injured, Hemingway never viewed himself as a powerless pawn in the cruel hands of fate — he instead embraced the trials he faced as testing points for his own manhood. His story is a good reminder that even though you can’t control what happens to you, you can always control how you write it into your life’s narrative and respond to it.

Hemingway’s life philosophy was that the world breaks everyone, but that men and women are made strong at the “broken places.” He realized that fortitude does not come from fleeing suffering, but by building brawn through hardship.

Strength is about having the courage to be vulnerable. It’s on the frontlines of war and life where you get injured the most, but also where you grow in courage. And when you boldly face the horrors of life, you become a beacon of light in a world of darkness.

If you enjoyed this email and want to support my work, the best way to do so is by purchasing a fresh bag of Imperium Coffee.

All the proceeds from Imperium go towards sharing more stories like this and helping others learn from the lives of great men — and since you’re on this list, you can use the code INVICTUS10 for 10% off your order!

Thanks as always for your support, and I look forward to seeing you on this week’s Spaces.

Ad finem fidelis,

Evan