November 12, 2024

Just six months after its enthusiastic declaration of independence, a fledgling American nation was on the brink of collapse.

British forces captured New York in a stunning victory, taking 3,000 American soldiers prisoner. The Continental Congress was forced to flee Philadelphia and relocate to Baltimore. American troops were mutinous, malnourished, and deserting in droves.

With the outcome of the war hanging in the balance, George Washington set out on a daring mission to take the fight to the British and change the course of history.

This is the story of how he led his men across the Delaware River and did just that…

The last months of 1776 had been a disaster for Washington. He lost Long Island, Manhattan, and Fort Washington to the British in quick succession, and was soon chased out of New York and New Jersey altogether.

His army had dwindled to less than 5,000 men — 2,000 of whom were sick, injured, or otherwise unable to fight. Men were deserting, and mutterings of mutiny flew across camp in the cold winter breeze.

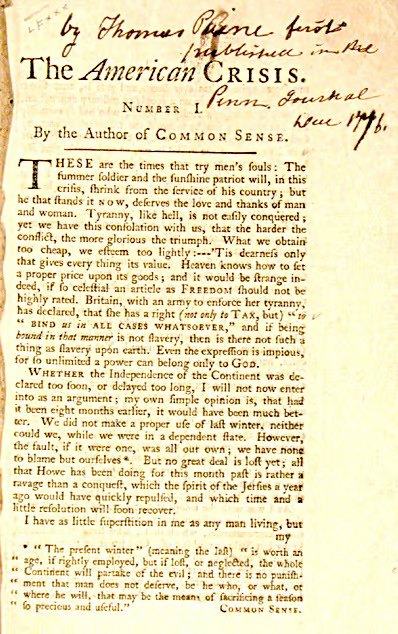

Washington knew that if he had any hope of survival, he had to bolster morale. He finally struck luck in December when Thomas Paine published a pamphlet entitled The American Crisis, in which he wrote:

These are the times that try men’s souls; the summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.

Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.

Washington ordered his troops to read the pamphlet in its entirety. Shortly after, a series of reinforcements arrived: first 2,000 men, then 600, and finally another 1,000.

With this, Washington finally had enough able-bodied men to muster a counter-attack. He had staved off defeat just long enough to get what he needed to act…

Spy intel helped Washington discern that Trenton, New Jersey was a vulnerable target. It lay on the other side of the ice-filled Delaware River, which served as a natural barrier — but the town itself was ill-equipped to defend against attack.

The main challenge lay in crossing the river, as doing so was a logistical nightmare. But here Washington’s leadership shone as he worked with locals to prepare. Experienced watermen were recruited to help navigate the crossing, and freight boats from Pennsylvania’s Durham Iron Works were repurposed to carry artillery and cavalry.

Three days before the crossing, Washington ordered one of his commanders to attack the British forces at Mount Holly, New Jersey. On the surface, it looked like a fool’s errand — 600 American soldiers facing down 2,000 British and Hessian troops.

The Americans lost the battle, but it was merely a pawn sacrificed in a larger game of chess. The attack worked as intended, drawing Hessian reinforcements far enough south that they wouldn’t be able to support the garrison at Trenton…

On Christmas night, 1776, Washington and his men marched towards the three embankment zones designated for the crossing. There was heavy snowfall when they arrived, and thick sheets of ice sprawled throughout the river.

The American forces set off in silence, with Washington himself crossing in one of the first boats. Upon reaching New Jersey, he set up a secure landing zone to receive the rest of the army. The password required to get through the line of sentries guarding the zone was “victory or death.”

Washington’s crossing was largely successful, with the majority of his men and artillery reaching the banks of New Jersey by 3:00am. The two other crossings, however, didn’t fare as well — ice had prevented them from getting through.

Washington was on his own, and at 4:00am he set off with his troops on the road to Trenton. The trek wasn’t easy, as a snowstorm made for a grueling nine miles. But what at first seemed like an ice-cold curse turned out to be a wonderful stroke of luck.

The Hessian mercenaries, thinking it unreasonable to expect an attack during a Christmas snowstorm, had spent the night drinking merrily. Their commander, Colonel Rall, was especially inebriated, and in no condition to lead.

So when Washington and his troops surprised the Hessians at daybreak, utter chaos ensued — it wasn’t so much of a battle as a one-sided throttling. The Americans easily overwhelmed the enemy forces, capturing 1,000 men while only losing three of their own. Colonel Rall himself was killed during the fighting.

Days later, Washington launched an assault on the nearby town of Princeton, where he won a second decisive victory. These back-to-back wins proved the Americans wouldn’t fold as easily as expected, and renewed faith in Washington’s leadership.

Although the war would last another five years, the crossing of the Delaware proved to be a linchpin in the American campaign. It helped stave off a quick defeat in the early stages of the war, and later served as inspiration when even tougher times — for example, the winter at Valley Forge — threatened to destroy morale.

Washington’s genius in crossing the Delaware didn’t lie in his military tactics, but in showing his men what fortitude, resolve, and courage looked like in the face of despair. It was a lesson that would ultimately carry them to victory — and to the founding of a new nation.

In the face of total defeat, Washington knew the worst risk was inaction. His Delaware crossing wasn’t a lucky act of desperation, but a bold move of genius. It brought the Americans a resounding victory and restored morale. Great success in life requires big, but calculated risks. Winners are bold, but not desperate.

Washington’s success was far from a one man show. He sought reinforcements from generals, delegated the logistics of crossing to experienced boatmen, and worked with locals to procure boats.

Washington didn’t have the expertise nor the resources required for the job, but he did have the humility and good sense to ask for help. A truly great endeavor should never be tackled alone — to achieve success, leverage relationships and the experience of others to help you do the impossible.

Washington didn’t rest after his victory at Trenton. He instead marched on Princeton, doubling down on his numerical advantage and the element of surprise to exploit his enemy’s weakness.

This second victory proved the first wasn’t a one-off, which boosted morale even further and restored Congress’ faith in Washington’s leadership. When you enjoy success in life, don’t get complacent — rather, double down on what’s working.

If you enjoyed this email and want to support me, the best way to do so is by picking up a fresh roast of coffee beans from our site.

All the proceeds from Imperium go towards sharing more stories like this and helping others learn from the lives of great men — and since you’re on this list, you can use the code INVICTUS10 for 10% off your order!

Thanks as always for your support, and I look forward to seeing you on this week’s Spaces.

Ad finem fidelis,

Evan